The many layers of the story of the women bent double in Luke 13

The lectionary gospel reading for Trinity 10 Year C is Luke 13.10–17, a remarkable short business relationship, unique to Luke, of Jesus healing a crippled woman on the Sabbath. At that place are multiple layers to the significant of this story, and an interesting and important claiming is how nosotros might, in our own local context, enable exploration of all these layers. A particularly hitting characteristic of this passage is the way that several aspects of it accept ane kind of significance in the original context of Jesus' ministry, but added significance in the Graeco-Roman context of Luke's readers.

The lectionary gospel reading for Trinity 10 Year C is Luke 13.10–17, a remarkable short business relationship, unique to Luke, of Jesus healing a crippled woman on the Sabbath. At that place are multiple layers to the significant of this story, and an interesting and important claiming is how nosotros might, in our own local context, enable exploration of all these layers. A particularly hitting characteristic of this passage is the way that several aspects of it accept ane kind of significance in the original context of Jesus' ministry, but added significance in the Graeco-Roman context of Luke's readers.

The context of this passage is the continuing mix of Jesus' miracles and his educational activity 'on the style' from Luke 9.51 until Jesus reaches Jerusalem in affiliate 19. Because nosotros don't accept in the narrative some of the obvious structural markers, like Matthew's division of Jesus' didactics into five sections, or the key turning point in Mark of the confession at Caesarea Philippi in Mark 8, information technology is piece of cake to see the material here as a slightly amorphous mixture, and our simply markers are the well-known episodes such as the Parable of the Good Samaritan in Luke 10 and the parables of the lost, including the so-chosen dissipated son in Luke xv.

Given this, and the fact (as we take previously noted) that Luke's geographical markers are very general, we need to sit up and take notice when Luke introduces this incident as taking identify 'in one of the synagogues'. This is the commencement mention of Jesus teaching in the synagogue since Luke 6.vi, when he likewise heals someone there on the Sabbath, and he never does so again in Luke—in fact, synagogues are mentioned less in Luke than they are in Acts, when Paul consistently proclaims the good news about Jesus in synagogues showtime, making it clear that the Jesus move is primarily a Jewish renewal motion before it is a Gentile move.

The most prominent mention of Jesus instruction in this context is dorsum in the synagogue in Nazareth in Luke 4.16, and we are therefore reminded of this programmatic incident. The connection is reinforced with the language that Jesus uses both to the woman in Luke xiii.12 and about her in Luke 13.16 of 'release', echoing the language of 'release of captives' in Luke 4.18 (though using slightly dissimilar vocabulary). Within Luke'southward overall narrative, this synagogue incident is once again enacting and demonstrating the kingdom ministry that Jesus proclaimed in the first synagogue incident.

The story itself has remarkably coherent literary construction to it, which some accept likened to a diptych, composed of two panels, in art.

| First panel | Second panel |

| Bent woman gets Jesus attention (13.11) | Synagogue ruler's words get Jesus' attention (13.14) |

| Jesus calls the woman and cures her (13.12–13a) | Jesus reacts to the ruler'south words (thirteen.fifteen–16) |

| Twofold results of Jesus' activeness (thirteen.13b) | Twofold results of Jesus' words (13.17) |

| a. Immediately she is made directly | a. Jesus' adversaries are put to shame |

| b. and she praises God | b. and all the people rejoice |

This structure has two chief furnishings. Start, it puts Jesus himself centre-phase in the narrative, emphasised by Jesus calling the woman to her rather than Jesus going to the woman. The story is all about the action of Jesus and reaction to Jesus. The second effect is that the enacting of the kingdom rule of God is put in stark parallel with the opposition that the coming of the kingdom volition provoke. This correlates with the other way that the 'synagogue' has featured so far in Luke'due south gospel; other than being a locus of Jesus' education, its most frequent mention has been as the context in which Jesus' followers will face up opposition (see Luke 12.eleven and 21.11), since information technology is the place where the Pharisees and teachers of the law love to drag themselves (Luke eleven.43 and xx.46). Given that this 'journey' section of Luke appears to exist all nearly discipleship, it is quite odd that the disciples feature then little in this center part—just the Pharisees are quite prominent, and Luke's main point hither appears to be that to follow Jesus means to face opposition.

Within the Jewish context of the original setting, two bug come to the fore.

The first is the question of the woman's illness and its relation to the work of Satan. Diverse discussions of her medical condition consistently conclude that she suffered from ankylosing spondylitis, an arthritic inflammation of the vertebrae which leads to curvature of the spine and progressive inability to flex the joints. At that place is still no cure for the condition. Only Luke uses some hitting linguistic communication in relation to he illness and its cure: she has a 'spirit of weakness' (NIV: 'has been crippled past a spirit', 5 xi) and Jesus' healing released her whom 'Satan has kept bound'. Nevertheless, in that location is no sense in which Luke records this (or that Jesus or others in the narrative perceive this) as exorcism from demon possession; the language of 'demon' or 'unclean spirit', and the actions of 'possession' and 'expelling', found in other gospel accounts of exorcism, and are all absent here. Rather, Jesus (with Luke) sees the physical and the spiritual as inextricably interlinked; it is hit that when she is physically able to stand and look upwards, she immediately breaks into praise to God. Joel Green comments (in his NICNT commentary, pp 521, 525):

From this ethnomedical perspective, and so, this adult female's illness has a physiological expression but is rooted in a cosmological disorder… [Jesus] regards his act of healing as an human action of liberation from satanic bondage, every bit directly engagement in cosmic disharmonize, through which God's eschatological purpose comes to fruition (run across Luke 11.twenty).

The second question is the estimation of the Fourth Commandment, to 'continue the Sabbath', and in the groundwork are the verses from the Torah:

Observe the Sabbath day by keeping it holy, as the LORD your God has commanded you. Vi days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh twenty-four hours is a sabbath to the LORD your God. On it you shall not practice any work..(Deut 5.12–14; compare Exod 20.ix).

The language of the synagogue leader is slightly obscured in freer English translations; his comment that 'there are six days on which it is necessary (dei) to piece of work' alludes to the command of God to work then and residue on the Sabbath. The question then becomes: who is the one with say-so to interpret the Torah, the 'law'? Luke is articulate in his respond to this by describing Jesus here as 'the Lord', not simply the Lord of the Sabbath (as Luke 6.5) but also the Lord of the meaning of the Torah, the authoritative interpreter. Luke here communicates something implicitly that is more explicit in, for example, Matt five–7, in which a very Jewish Jesus brings out the full meaning of the scriptures, and emphasises that he is not in any sense nullifying them or setting them aside. Hither, Jesus' interpretative strategy is to read on, and more than fully, to empathise the theological principle of Sabbath observance rather than offering a mere surface reading. His response but continues reading Deut 5 into its firsthand context:

On it you shall not do any work, neither you, nor your son or daughter, nor your male or female person servant, nor your ox, your ass or any of your animals, nor whatsoever foreigner residing in your towns, so that your male person and female servants may rest, every bit you do. Remember that you were slaves in Arab republic of egypt and that the LORD your God brought you out of in that location with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. Therefore the LORD your God has commanded you to observe the Sabbath day. (Deut 5.14–15)

Sabbath means remainder and liberation, not only for God's people only also for the 'ox and the donkey' that Jesus mentions. He argues here from the lesser to the greater; if you are prepared to offer Sabbath rest to your animals, surely you cannot withhold this from a person? The Sabbath itself is a reminder of the release from captivity that God has effected—and so Jesus' release of this woman is a sign of the new Sabbath as a result of the new Exodus that Jesus will accomplish (Luke 9.31).

In the Graeco-Roman context of Luke and his readers, two rather dissimilar issues arise.

The kickoff is the issue of physiognomics, by which aboriginal writers, physicians and philosophers believed that different parts of the body, and their condition, indicated something about a person's inner life and identity—so, for example, ankles were supposed to point something important almost character, with strong ankles indicative of a strong and reliable character (think Achilles and his arrow). Despite claims to the contrary, information technology seems that our visual culture, shaped past the net, also values people in relation to their advent.

The connection between the inner and the outer in Luke's language of the 'spirit of weakness' existence the apparent cause of the adult female's condition might at first look equally though it plays into this perception of the earth. Mikeal Parsons, in his Paideia commentary (p 217) notes the comment of pseudo-Aristotle'southPhysiognomics:

Those whose back is very large and strong are of strong character; witness the male. Those which have a narrow, weak back are feeble; witness the female.

Physiognomy would also extend to the mention of the 'ox and the ass'; pseudo-Aristotle comments:

Those that have thick extremities to the nostrils are lazy; witness cattle…and those with think faces are conscientious, with fleshiness are cowardly, witness donkeys and deer. (cited in Parsons, p 218)

And yet Jesus defies this kind of stereotyping in two ways. First, the affliction of the woman comes from without, from a spirit and the bondage of Satan, and not from within, the result of her own graphic symbol flaw. Secondly, in response to the criticism, Jesus describes the adult female as a 'daughter of Abraham', a unique designation used of no-i else, but connected with a consistent theme of the question of true Jewish identity introduced in the language of 'Abraham and his offspring' in Luke i.55 and in the pedagogy of John the Baptist in Luke iii.8–ix.

The second is the issue of honour and shame in the Roman world. Where the crippled adult female would have been an object of shame, and those in the places of power would exist people of honour, Jesus' action and teaching effect a reversal in these ii states. The adult female now is honoured in the way Jesus describes here, and information technology is very striking that the oversupply rejoice in the fact that, through Jesus' words, 'all his opponents were shamed' (Luke 13.17). This is not about mere petty vengeance; it is most Luke communicating who is truly honoured and shamed in a social context where this values were of defining importance. Despite the dominant cultural view, it is actually (before God) those who follow Jesus who have the place of true honour, in contrast to all appearances to the reverse.

Two final issues are worth noting.

The first is another fascinating example of numerology. The number xviii occurs only in this chapter in the whole New Attestation, and Luke emphasises information technology not only past mentioning it twice here (in verses xi and 16; it too occurs in the previous episode in Luke 13.iv) just past using ii different phrase on the two occasions, δεκαοκτὼ and δέκα καὶ ὀκτὼ (x-eight and 'x and eight'). Why might this exist pregnant? Because, equally Mikeal Parsons shows in a fascinating study in numerology, xviii is the value of the outset two messages of Jesus' proper noun, iota and eta, and in one manuscript tradition, the number eighteen is actually written iota-eta, with a line over it, which corresponds to anomen sacrum, an abbreviation normally used in manuscripts for the holy proper noun of Jesus and of God. In emphasising this number, Luke is challenge that Jesus is the appointed cure of her ailment.

This interpretation is reinforced by 1 of the earliest papyrus witnesses to Luke, Chester Beatty Papyrus I, better known equally P45…At both 13:11 and 13:16, the number "eighteen" is written equally ιη, with an over stroke to indicate the letters are serving as a number. Besides, in 13:14, the name of "Jesus" is written in the same way, ιη, also with an over stroke, here though to indicate the nominum [sic] sacrum. The consequence is a purely visual miracle in which the reader of P45 would meet the same abbreviation, ιη, for both "18" and "Jesus," reinforcing our Christological interpretation of the number eighteen in Jesus' response in xiii:16…

Given the presumed propensity to equate the number eighteen (or better "ten and 8") with Jesus, at to the lowest degree in some circles, this form drew attention to the number and was the aural equivalent to the visual miracle. Thus, an audience hearing Luke thirteen could have the experience in identifying the eighteen years of Luke 13:16 with Jesus, an experience not altogether unlike the i enjoyed by the actual reader of the symbols on the page. In this reading, not only is the woman's true character made manifest in the healing, so is the identity of Jesus revealed in the very number associated with the length of her illness.

Secondly, although the kingdom and eschatological promise are not mentioned inside this passage, it is implied from the context of the surrounding passages which emphasise the sectionalization that will come with God's judgement—and the verses that immediately follow. Again, English translations, and the divisions in the lectionary, might throw us off the scent—just Luke is quite clear, when he introduces Jesus' didactics about the kingdom every bit a mustard seed and as yeast in the flour with a strong 'Therefore…' in Luke thirteen.18. This education needs to be read as an exposition by Jesus of what has just happened in his kingdom-demonstrating ministry.

Gear up in relation to the healing episode of vv 10–17, this parable [of the kingdom and the yeast in flour] declares that satanic domination is being repealed and the kingdom of God is made present even in such seemingly inconsequential acts as the restoration of an ill adult female who lived on the margins of social club. (Joel Green, NICNT, p 527).

How might nosotros enable our congregations to explore all these fascinating issues? Over again, Mikeal Parsons anticipates this problem in his study of numerology and the use of thenomen sacra as the number eighteen:

The reception of early Christian texts was primarily in an oral and communal context, that is, the texts were read aloud by a lector to a community probably gathered together for a meal and some kind of edifying activity (eastward.g.,worship, etc.). Thus, Luke surely causeless that his text would take been read aloud and so discussed, every bit was the custom of the 24-hour interval. This process would have allowed for the subsequent examination and explication of the text. This context would have provided the occasion for the interpreter to communicate orally this visual phenomenon. The manuscript evidence supports this position.

Perhaps we should be doing the same?

Additional note:

In online discussion, I have been asked how we might preach on some of these ideas, especially the observation about numerology. I offer hither several brief observations.

The links in the passage to the earlier educational activity of Jesus in the Nazareth synagogue makes a connectedness betwixt Jesus' words and his actions. The breaking in of the kingdom of God does involve announcement, just it as well involves things happening, and the two need to match each other. As Paul says in 1 Cor 4.20, 'The kingdom of God is not about talk only about power'. We live in an historic period where talk is easy, especially online; whether actions match our words is another matter. And a key frustration of outsiders with Christians and the church is when they are all talk and no action. Does Christian faith really make a deviation in our life?

The symmetry betwixt Jesus' response to the woman and Jesus' response to his critics is part of Luke's consistent accent that the kingdom will bring opposition and then Jesus' followers, faithful in kingdom living and proclamation, will confront hostility. Of course, it is e'er possible that this will arise because nosotros are being crass and insensitive! Merely if we are seeking to live faithfully to Jesus, nosotros should not be surprised when difficulties comes.

The fact that the woman'southward healing is for Jesus a sign of the presence of the kingdom of God demonstrates one time once more (and in line with the 'Nazareth Manifesto') how broad the concerns of the kingdom are. 'The kingdom of God is creation healed', and so we need to be open to God's working past his Spirit in all sorts of aspects of life.

Jesus is presented as the administrative interpreter of the Old Testament law. Jesus neither sets aside Torah nor simply follows it slavishly in the style his contemporaries practise, simply reads it holistically and theologically, drawing out its total significant. We demand to avoid separating Jesus and the telephone call to follow him from the teaching of the Old Attestation which he comes to 'fulfil'.

Information technology is worth noting the manner that Luke tells the story in a way that makes sense in his cultural context, and brings out implications for his readers—for nosotros are in a similar situation of being in a context removed from the original setting. Just we besides alive in a earth that is shaped by physiognomy: tall people are more than likely to be promoted to positions of leadership; people with deep voices seem more than trustworthy to us; ugly people are more likely to be bedevilled in court; and we might discover how differently nosotros answer to attractive people that we see. Those who exercise influence in media, sports, business and politics do and so in big role because of their appearance, and this has been accentuated in our highly visual media and cyberspace age. 'The LORD does not look at the things human beings await at. People look at the outward appearance, only the LORD looks at the heart' (1 Sam 16.7).

The numerology might exist the about challenging to brand use of in preaching. But finding a mode of explaining it does aid the states to be enlightened that the Bible is written in some other culture from us, and in some important senses is a 'strange' text to us. But the implications are annihilation but foreign; in making this connection betwixt the woman's condition and the name of Jesus, he is saying to united states that Jesus was ever going to be the only reply to this incurable condition. I think Paul would say the same about our sin and alienation from God.

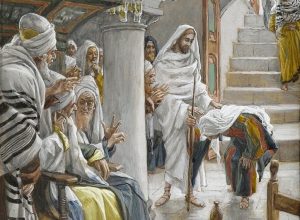

The illustration at the head of this article is a section from a painting past James Tissot, a nineteenth-century French painter and illustrator who moved to London in 1871. He was close to the Impressionists, and was invited to be role of the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, but he declined and (in contrast to other French painters), moved to a more realistic, rather than impressionistic, manner of painting. Afterwards moving to London, in 1885 he experienced a renewal of his Roman Cosmic faith, and devoted himself to painting scenes from the Bible, aided by travelling to the Middle East. He created a serial of 365 painting of the life and ministry of Jesus, of which this is one, and was working on a series on the Old Testament when he died. I honey the dynamic and light of the picture, and the way the two scenes either side of the pillar match the 'diptych' narrative construction of the passage. Jesus would, of course, have been sitting to teach, but mayhap he stands to heal the adult female.

If you enjoyed this, do share it on social media, possibly using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo.Similar my page on Facebook.

Much of my work is done on a freelance basis. If you have valued this post, would y'all consideraltruistic £one.20 a month to support the product of this blog?

If you lot enjoyed this, practice share information technology on social media (Facebook or Twitter) using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo. Like my folio on Facebook.

Much of my work is done on a freelance basis. If you lot have valued this post, you tin make a single or repeat donation through PayPal:

Comments policy: Good comments that appoint with the content of the post, and share in respectful debate, can add real value. Seek first to understand, then to exist understood. Make the most charitable construal of the views of others and seek to learn from their perspectives. Don't view debate every bit a conflict to win; address the argument rather than tackling the person.

Source: https://www.psephizo.com/biblical-studies/the-many-layers-of-the-story-of-the-women-bent-double-in-luke-13/

0 Response to "The many layers of the story of the women bent double in Luke 13"

Publicar un comentario